Recent websplorations have led me to this:

Factorization Diagram

which will eventually lead me to buy this:

Factorization Diagram Print

and spend way to much time watching and thinking about this:

Factorization Diagram Visualization

and exploring here:

Data Pointed

and especially here:

Visualizations

Tuesday, October 6, 2015

Thursday, October 1, 2015

Another Reason to Flip

As I consider moving to a flipped classroom I am reminded of another benefit. Every one of my classes consists of students sitting at distance learning centers as well as my F2F students. Often, the students at the distance sites are not involved at all and sit through the entire semester without participating in the class.

In a flipped classroom it would be possible to take time to devote entirely to these distance students. While all students are working on problems and activities it would be possible for me to engage my distance students directly. I have never found another way to do this. It is becoming more and more evident that flipping is going to happen.

Tuesday, September 22, 2015

Math Instructional Practices

Maria Anderson summarizes the various approaches to teaching found in most undergraduate math classes:

Math Instruction Practices

Math Instruction Practices

Friday, September 18, 2015

A Busy Professor's Guide to Sanely Flipping Your Class - Dr. Cynthia Furse

Some great thoughts on why and how to flip. First-hand experiences shared and key experiences given.

Video

Video

First the Theory

Returning to the cheesemonkeysf summation of How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School now with a discussion of the four stages being advocated.

The stages (as summarized by cheesemonkeysf) are:

(Now isn't that a pretty copy and paste from THIS post?)

I would like to flesh out some of these ideas, highlight some of the language that is meaningful, and then explore how this might look in a REAL classroom. This post will be the "fleshing out" post. Let's start with Stage 1.

Stage 1 - Students arrive in class rarely ready to engage with the material. Their minds are elsewhere (probably Facebook) and they don't switch their thinking quickly. This is the reality of education. As a result, something needs to be done to help students switch from "whatever the heck a teenager/student/working adult" thinks about to the topic at hand.

There are at least two components to helping students make this switch when they enter your classroom: 1) a successful introductory task and 2) consistency.

Something needs to be done to get the students' attention. A task, a video, a question, a discussion, a story, something. Perhaps the task is related to the material for the day and perhaps it isn't (more on this later) but something needs to be done BEFORE you can start teaching. If the task isn't directly related to the content of the day there should be something about it that asks them to think and move into an academic mindset.

More of cheesemonkeysf's commentary on Stage 1:

STAGE 1

A good discovery activity can be a powerful catalyst for learning in Stage 1. But unfortunately, sometimes there just really isn't a great discovery activity that leads students captivatingly but inexorably to a blinding insight that will transform their learning forever.

Sometimes the best you've got is a mediocre discovery activity from a textbook that kinda sorta leads students in the general direction — but not without a lot of heavy-handed guidance. Or perhaps there is some other deficiency in what is available to you.

Like Gattegno, I believe that all learners have an energy "budget," and that means I have to make savvy and strategic decisions about how I'm going to ask my students to apply theirs. A boring or mediocre discovery activity can take just as much energy as a great one, but without the payoff of leaving students energized.

So sometimes I've learned I have to ask myself, is a discovery activity thebest choice I can make here at Stage 1? Or do I have some other kind of introductory task I could use — such as a simulation, a story, a funny or interesting deleted scene, or some other kind of analogy — that will get my class into the learning episode faster and free up more of their energies to developing the necessary fluency that a rich and interesting transfer task may require?

To me, the most important thing that can happen in Stage 1 of a learning episode is that students come sharply to appreciate the Burning Question of this segment. Whenever possible, I really like for my students to arrive at a Burning Question through a collaborative discovery activity that they own because when they own it, they buy into it.

But realistically, this is simply not always possible with every single topic in the curriculum. So I have a range of strategies for Stage 1 that can get my students to a Burning Question even though there may be a gap in my pedagogical arsenal.

Key phrases for further consideration and exploration - "catalyst for learning", may not be an activity to is captivating, "energy budget", a mediocre activity may only be just as good as a bad activity, perhaps there are other activities that will get the class into the "learning episode" and save energy for other necessary activities, "students come sharply to appreciate the Burning Question", "uncover and organize prior knowledge", "provide occasion for exploratory talk", "not always possible with every single topic", have a range of strategies that can get student to a Burning Question.

The stages (as summarized by cheesemonkeysf) are:

STAGE 1 - a hands-on introductory task designed to uncover & organize prior knowledge. In this stage, collaborative activity provides an occasion for exploratory talk so that students can uncover and begin to organize their existing knowledge;

STAGE 2 - initial provision of a new expert model, with scaffolding & metacognitive practices woven together. The goal here is to help students bring their new ideas and knowledge into clearer focus so that they can reach the next level. Here again, collaborative activity can provide a setting in which to externalize mental processes and to negotiate understanding, although often, this can be a good place to offer some direct instruction;

STAGE 3 - what HPL refers to as "'deliberate practice' with metacognitive self-monitoring." Here the idea is to use cooperative learning structures to create a place of practice in which learners can work within a clearly defined structure in which they can advance through the 3 stages of fluency (effortful -> relatively effortless -> automatic)

STAGE 4 - working through a transfer task (or tasks) to apply and extend their new knowledge in new and non-routine contexts.

(Now isn't that a pretty copy and paste from THIS post?)

I would like to flesh out some of these ideas, highlight some of the language that is meaningful, and then explore how this might look in a REAL classroom. This post will be the "fleshing out" post. Let's start with Stage 1.

Stage 1 - Students arrive in class rarely ready to engage with the material. Their minds are elsewhere (probably Facebook) and they don't switch their thinking quickly. This is the reality of education. As a result, something needs to be done to help students switch from "whatever the heck a teenager/student/working adult" thinks about to the topic at hand.

There are at least two components to helping students make this switch when they enter your classroom: 1) a successful introductory task and 2) consistency.

Something needs to be done to get the students' attention. A task, a video, a question, a discussion, a story, something. Perhaps the task is related to the material for the day and perhaps it isn't (more on this later) but something needs to be done BEFORE you can start teaching. If the task isn't directly related to the content of the day there should be something about it that asks them to think and move into an academic mindset.

More of cheesemonkeysf's commentary on Stage 1:

STAGE 1

A good discovery activity can be a powerful catalyst for learning in Stage 1. But unfortunately, sometimes there just really isn't a great discovery activity that leads students captivatingly but inexorably to a blinding insight that will transform their learning forever.

Sometimes the best you've got is a mediocre discovery activity from a textbook that kinda sorta leads students in the general direction — but not without a lot of heavy-handed guidance. Or perhaps there is some other deficiency in what is available to you.

Like Gattegno, I believe that all learners have an energy "budget," and that means I have to make savvy and strategic decisions about how I'm going to ask my students to apply theirs. A boring or mediocre discovery activity can take just as much energy as a great one, but without the payoff of leaving students energized.

So sometimes I've learned I have to ask myself, is a discovery activity thebest choice I can make here at Stage 1? Or do I have some other kind of introductory task I could use — such as a simulation, a story, a funny or interesting deleted scene, or some other kind of analogy — that will get my class into the learning episode faster and free up more of their energies to developing the necessary fluency that a rich and interesting transfer task may require?

To me, the most important thing that can happen in Stage 1 of a learning episode is that students come sharply to appreciate the Burning Question of this segment. Whenever possible, I really like for my students to arrive at a Burning Question through a collaborative discovery activity that they own because when they own it, they buy into it.

But realistically, this is simply not always possible with every single topic in the curriculum. So I have a range of strategies for Stage 1 that can get my students to a Burning Question even though there may be a gap in my pedagogical arsenal.

Key phrases for further consideration and exploration - "catalyst for learning", may not be an activity to is captivating, "energy budget", a mediocre activity may only be just as good as a bad activity, perhaps there are other activities that will get the class into the "learning episode" and save energy for other necessary activities, "students come sharply to appreciate the Burning Question", "uncover and organize prior knowledge", "provide occasion for exploratory talk", "not always possible with every single topic", have a range of strategies that can get student to a Burning Question.

Wednesday, September 16, 2015

First Day Activity and Discussion - Maze Moments

This might be an appropriate thing to do on the first day of class. Solve mazes, discuss problem solving strategies, and relate all of that to solving math problems.

Maze Moments

Maze Moments

How People Learn

cheesmonkeysf (I assume this is not her real name.) provides a great summary of "How People Learn" in this post:

"How People Learn" and how people learn

"How People Learn" and how people learn

Choosing a Teaching Approach

It takes about 2 seconds in the teaching profession before you start asking yourself "Should I be doing something different?" Now, don't think I'm talking about the desire for a different career choice. Perhaps the more accurate question is "Should I be doing something different in the classroom?"

There are many reasons we are constantly assailed by this question as teachers: the desire to be more effective; the frustration of seeing students fail or show only minimal signs of life; administrators signing up for new programs; or the constant barrage of new ideas about teaching that are always being advocated.

So what is a teacher to day? Here are some suggestions purely from my own experience and lacking any sort of reference.

1. Play to your strengths. If you do something well that no one else does then make sure your plan always includes that strength.

2. Don't feel the need to be original. Some teachers feel like unless they are using a method that they developed themselves then they really aren't teaching. Not true. It is perfectly fine to use materials, ideas, philosophies, etc. that have already been created or developed. Using these already-existing materials allows you to free up more time to do things YOU are good at.

3. Develop the ability to ignore ideas. Not everything (even the great ideas) you discover can or should be implemented in your classes. It's okay to say "Wow, that's a great idea! But I am not going to use it because I am doing something else." It's not necessary (and clearly it is impossible) to use all of the great ideas that are out there.

4. Put your own twist on things. If you find a good idea you want to use accept the fact that you will need to change the idea in some way to work for you. Your personal and classroom circumstances will almost always be different that those of the creator of the idea. It's just fine to take an idea and implement only a small portion of it that fits. Nothing is set in stone.

5. Enjoy and value what you do do (hee-hee) in class. There has never been nor will there ever be a perfect class. Saying to yourself "when I get this approach mastered or when I have totally polished this lesson plan, then I will feel like I am effective" is a first step to burn-out and frustration. Each and every day, whether you feel 100% prepared or not, you get the chance to talk about a topic you enjoy and spend some time with students who you care about. That's a pretty good day job. Enjoy it and don't wait for things to be perfect to do so.

6. Never make a list with more than 5 items.

These are just some thoughts I've had and perhaps will find some literature on the topic for the future.

There are many reasons we are constantly assailed by this question as teachers: the desire to be more effective; the frustration of seeing students fail or show only minimal signs of life; administrators signing up for new programs; or the constant barrage of new ideas about teaching that are always being advocated.

So what is a teacher to day? Here are some suggestions purely from my own experience and lacking any sort of reference.

1. Play to your strengths. If you do something well that no one else does then make sure your plan always includes that strength.

2. Don't feel the need to be original. Some teachers feel like unless they are using a method that they developed themselves then they really aren't teaching. Not true. It is perfectly fine to use materials, ideas, philosophies, etc. that have already been created or developed. Using these already-existing materials allows you to free up more time to do things YOU are good at.

3. Develop the ability to ignore ideas. Not everything (even the great ideas) you discover can or should be implemented in your classes. It's okay to say "Wow, that's a great idea! But I am not going to use it because I am doing something else." It's not necessary (and clearly it is impossible) to use all of the great ideas that are out there.

4. Put your own twist on things. If you find a good idea you want to use accept the fact that you will need to change the idea in some way to work for you. Your personal and classroom circumstances will almost always be different that those of the creator of the idea. It's just fine to take an idea and implement only a small portion of it that fits. Nothing is set in stone.

5. Enjoy and value what you do do (hee-hee) in class. There has never been nor will there ever be a perfect class. Saying to yourself "when I get this approach mastered or when I have totally polished this lesson plan, then I will feel like I am effective" is a first step to burn-out and frustration. Each and every day, whether you feel 100% prepared or not, you get the chance to talk about a topic you enjoy and spend some time with students who you care about. That's a pretty good day job. Enjoy it and don't wait for things to be perfect to do so.

6. Never make a list with more than 5 items.

These are just some thoughts I've had and perhaps will find some literature on the topic for the future.

Wednesday, April 8, 2015

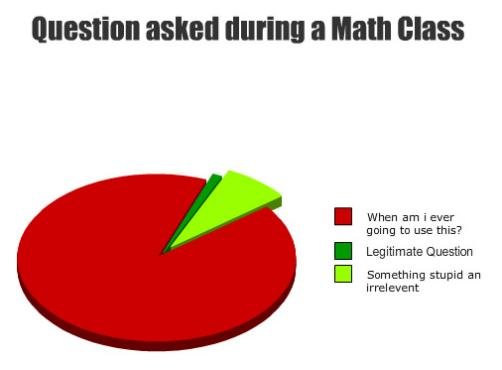

It's Not About the Question

Every math teacher eventually gets asked THE question. You know the question I mean. You are thinking of it right now. It is the dreaded "When am I ever going to use this stuff?" question. I am here to tell you that this question isn't a question at all. Sometimes this question is a trap asked by a student who is anxious to scoff at the canned answers math teachers are programmed to give ("you might want to become an engineer", "in our modern world you have to know math", "this is helping you become a better critical thinker", etc.). Sometimes the question is an act of defiance asked by a student so frustrated with what is being taught and feeling so powerless in math's mighty wake that they politely ask the question instead of standing up and screaming "I'm mad as Hell and I'm not going to take it anymore." And occasionally this question is genuine asked by a student who is genuinely interested in the applications they are learning and is excited by the possibilities. The problem with this question is that it is ill-posed. It can't be answered with a black-or-white answers because the real answers are actually many shades of gray (spank!) and leave both students and teachers unfulfilled. More likely, the question shouldn't even be answered at all because it is Not. Actually. About. The Question.

Every math teacher eventually gets asked THE question. You know the question I mean. You are thinking of it right now. It is the dreaded "When am I ever going to use this stuff?" question. I am here to tell you that this question isn't a question at all. Sometimes this question is a trap asked by a student who is anxious to scoff at the canned answers math teachers are programmed to give ("you might want to become an engineer", "in our modern world you have to know math", "this is helping you become a better critical thinker", etc.). Sometimes the question is an act of defiance asked by a student so frustrated with what is being taught and feeling so powerless in math's mighty wake that they politely ask the question instead of standing up and screaming "I'm mad as Hell and I'm not going to take it anymore." And occasionally this question is genuine asked by a student who is genuinely interested in the applications they are learning and is excited by the possibilities. The problem with this question is that it is ill-posed. It can't be answered with a black-or-white answers because the real answers are actually many shades of gray (spank!) and leave both students and teachers unfulfilled. More likely, the question shouldn't even be answered at all because it is Not. Actually. About. The Question.

When I hear this question in my classes it usually comes from students that are struggling and are showing signs of frustration. Rarely does this question come from a student that is doing well in the class, but if it does you can often hear an exclamation at the beginning and at the end of the statement which conveys a sincere question, as in "Wow! When will I get to use this? It's soooo cool!" When a frustrated student asks the question it's my belief that they aren't 100% really wanting an answer. Rather, what they are doing is trying to use a politically correct way to say "This sucks! I don't understand! I don't see the point of wasting any more time and I'm hoping there are some other students who will jump on my frustration bandwagon so I can feel some support. Because if, in this democratic society, I get enough supporters to my cause then we win and can all confidently declare this experience as a waste of time and stop investing our valuable time and energy." I can hear these underlying sentiments practically every time a student lobs this out.

After all of these years, I have accepted that "It's not about the question". If I forget this and try to "answer" I find myself repeating the trite phrases mentioned above that invariably induce unconvinced eye-rolls. In an effort to deal with this question I have occasionally found myself changing my curriculum, adding lots of real-life projects and problems, just so that when someone asks the question I can point to the problems and say "Ha! See! We are using math to solve real problems. Take that!". Another possible reaction is to raise my arms in surrender, stop teaching so many abstract ideas that often inspire the question, and adopt content that will not be so frustrating to the students (I'm looking at you Sudoku, Gamification (is it ironic that spell check wants to change this to Gasification?), and 3 Act Math). I'm not saying any of these are bad teaching tools; in fact, I like them all. I am simply saying that they don't necessarily help those question-asking, frustrated students stop asking the question and that they are incomplete solutions when taken to the extreme.

I believe that what a student is really saying when they ask this question is "Where is my place in the mathematical world?" They might add, if pressed, "I am so frustrated and confused that I don't feel like I can participate in these mathematical activities at all. Are there mathematical ideas that I can understand and if so, what are they?" I don't think students want to be locked out of the mathematical world and when they feel locked out their only defense (if only to safeguard their self-confidence/respect/efficacy) is to try and purposefully categorize the mathematical world as alien and unnecessary. If, on the other hand, they were introduced to ideas that they could grasp and make their own, they would be so busy with those ideas that the question of later application wouldn't cross their mind. Or, if it did, it would be in the form of "Wow! When will I get to use this? It's soooo cool!"

All of this is to say: I believe that math teachers should worry less about trying to answer the question and should worry more about finding ways for each student to feel that they are part of the mathematical world. For some it might take applications, for others it might take games, and for others it might actually take old-fashioned algebra problems. Whoever the student there should be some mathematical or mathematical-like idea that resonates with them. And then once we have a place to start with each student we can begin to introduce them to the next idea and so on and so on. Let's stop worrying so much about answering "the question" and start spending more time finding mathematical ideas that each student can call their own.

All of this is to say: I believe that math teachers should worry less about trying to answer the question and should worry more about finding ways for each student to feel that they are part of the mathematical world. For some it might take applications, for others it might take games, and for others it might actually take old-fashioned algebra problems. Whoever the student there should be some mathematical or mathematical-like idea that resonates with them. And then once we have a place to start with each student we can begin to introduce them to the next idea and so on and so on. Let's stop worrying so much about answering "the question" and start spending more time finding mathematical ideas that each student can call their own.Friday, April 3, 2015

Active Learning is the Goal

College math classes have a reputation of being lecture-based. Actually it might be even more accurate to say that the classes are typically lecture-only. Why? There are probably many reasons: lecturing is easy (especially after you have taught a class many times), math professors grew up listening to (and learning from) lectures, math professors are often unfamiliar with teaching methods and strategies, and lecturing fits nicely with the time and content constraints of the modern sequential college pre-calculus curriculum. There are probably many other reasons. But the point is, we tend to fall into the lecture rut in college math classes.

Lecturing is 1) only effective/interesting in small doses and 2) not the most efficient method of transferring knowledge. Freeman et al. found that active learning was better than lecturing in helping students pass (learn?) as shown in the accompanying graph.

So none of this is new, of course. But finding the best methods for incorporating active learning into my classrooms is a constant challenge. Finding the time during the already-packed semester to incorporate the ideas, motivating students to take advantage of the activities, and convincing students that they might actually learn something are all big hurdles. All of the challenges are amplified by the fact that my students are often well behind their peers in terms of mathematical preparation. The lack of content knowledge is coupled with many years of bad experiences in math classes. Not only do I need to find the best ways to teach the material but I also need to help students believe that they can learn the material.

One last factor that I must confront with my students is cultural. My classes typically have between 40-70% Navajo students with the rest being Caucasian. My Navajo students rarely speak up to ask questions and often take a backseat, in terms of participation, to the Caucasian students who are more comfortable voicing their thoughts. I realize these are broad strokes but they tend to be true and force me to consider ways to involve my Native students. Active learning in small groups provides some hope as I can group my students such that everyone's voice is heard.

Thursday, April 2, 2015

One of My Inspirations

Part of the challenge (at least for me) to beginning a blog is 1) not feeling like you have anything to post and 2) not wanting to post "beginner" posts that aren't insightful and that will possibly be looked back on over time with a bit of embarrassment for their pedestrian nature. In other words I don't want to look like an idiot for the months/years/decades (yikes!) that it might take for me to become proficient and skilled at this medium. Well here is my confession...I am willing to look like an idiot if it will help me in the long run. So, dear reader, I hope you enjoy these elementary posts until I have something more interesting to offer.

So the question I had was whether there were other blogs out there that started from scratch without the fear of public scorn and have grown into something very great and contributory to the math community. I did some searching around and found lots of blogs that were posting great things. Then I went back in the history of those blogs and checked out their early posts to see if there was any hope for someone starting from pure nothing. Here is one of the blogs that I discovered:

First of all, I found that this blog was current and had been active for nearly 10 years. That's a long time. Second, I found that I really liked reading this blog. And lastly, I checked back into the seedy history of this blog and found a teacher who started off small as a blogger, stuck with it, and developed into a great blogging. It truly appears that this teacher's blog is an important part of her teaching practice and reflection. If you have a chance, check it out.

Navigating the Whirlwind

Now is a great time to be a math teacher (yes, I'm pretending to ignore the Math Wars, Common Core, decreasing funding, increasing testing, etc.). Why do I say this? Because my Twitter Feed and my Pocket page and my Pinterest account are bulging with incredible math ideas, opinions, and resources. There is so much out there that it becomes critical that an educator find a way to organize it. This blog is my attempt at just such a task. I want to remember and expand on some of the ideas that I find in an effort to improve my teaching.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)