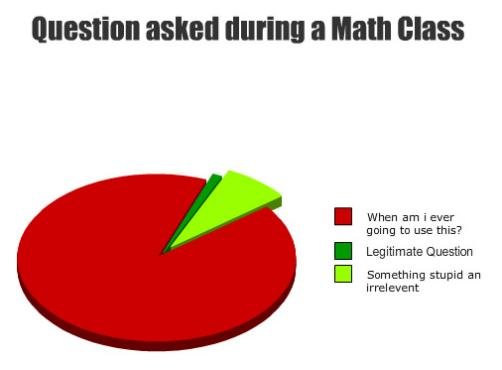

Every math teacher eventually gets asked THE question. You know the question I mean. You are thinking of it right now. It is the dreaded "When am I ever going to use this stuff?" question. I am here to tell you that this question isn't a question at all. Sometimes this question is a trap asked by a student who is anxious to scoff at the canned answers math teachers are programmed to give ("you might want to become an engineer", "in our modern world you have to know math", "this is helping you become a better critical thinker", etc.). Sometimes the question is an act of defiance asked by a student so frustrated with what is being taught and feeling so powerless in math's mighty wake that they politely ask the question instead of standing up and screaming "I'm mad as Hell and I'm not going to take it anymore." And occasionally this question is genuine asked by a student who is genuinely interested in the applications they are learning and is excited by the possibilities. The problem with this question is that it is ill-posed. It can't be answered with a black-or-white answers because the real answers are actually many shades of gray (spank!) and leave both students and teachers unfulfilled. More likely, the question shouldn't even be answered at all because it is Not. Actually. About. The Question.

Every math teacher eventually gets asked THE question. You know the question I mean. You are thinking of it right now. It is the dreaded "When am I ever going to use this stuff?" question. I am here to tell you that this question isn't a question at all. Sometimes this question is a trap asked by a student who is anxious to scoff at the canned answers math teachers are programmed to give ("you might want to become an engineer", "in our modern world you have to know math", "this is helping you become a better critical thinker", etc.). Sometimes the question is an act of defiance asked by a student so frustrated with what is being taught and feeling so powerless in math's mighty wake that they politely ask the question instead of standing up and screaming "I'm mad as Hell and I'm not going to take it anymore." And occasionally this question is genuine asked by a student who is genuinely interested in the applications they are learning and is excited by the possibilities. The problem with this question is that it is ill-posed. It can't be answered with a black-or-white answers because the real answers are actually many shades of gray (spank!) and leave both students and teachers unfulfilled. More likely, the question shouldn't even be answered at all because it is Not. Actually. About. The Question.

When I hear this question in my classes it usually comes from students that are struggling and are showing signs of frustration. Rarely does this question come from a student that is doing well in the class, but if it does you can often hear an exclamation at the beginning and at the end of the statement which conveys a sincere question, as in "Wow! When will I get to use this? It's soooo cool!" When a frustrated student asks the question it's my belief that they aren't 100% really wanting an answer. Rather, what they are doing is trying to use a politically correct way to say "This sucks! I don't understand! I don't see the point of wasting any more time and I'm hoping there are some other students who will jump on my frustration bandwagon so I can feel some support. Because if, in this democratic society, I get enough supporters to my cause then we win and can all confidently declare this experience as a waste of time and stop investing our valuable time and energy." I can hear these underlying sentiments practically every time a student lobs this out.

After all of these years, I have accepted that "It's not about the question". If I forget this and try to "answer" I find myself repeating the trite phrases mentioned above that invariably induce unconvinced eye-rolls. In an effort to deal with this question I have occasionally found myself changing my curriculum, adding lots of real-life projects and problems, just so that when someone asks the question I can point to the problems and say "Ha! See! We are using math to solve real problems. Take that!". Another possible reaction is to raise my arms in surrender, stop teaching so many abstract ideas that often inspire the question, and adopt content that will not be so frustrating to the students (I'm looking at you Sudoku, Gamification (is it ironic that spell check wants to change this to Gasification?), and 3 Act Math). I'm not saying any of these are bad teaching tools; in fact, I like them all. I am simply saying that they don't necessarily help those question-asking, frustrated students stop asking the question and that they are incomplete solutions when taken to the extreme.

I believe that what a student is really saying when they ask this question is "Where is my place in the mathematical world?" They might add, if pressed, "I am so frustrated and confused that I don't feel like I can participate in these mathematical activities at all. Are there mathematical ideas that I can understand and if so, what are they?" I don't think students want to be locked out of the mathematical world and when they feel locked out their only defense (if only to safeguard their self-confidence/respect/efficacy) is to try and purposefully categorize the mathematical world as alien and unnecessary. If, on the other hand, they were introduced to ideas that they could grasp and make their own, they would be so busy with those ideas that the question of later application wouldn't cross their mind. Or, if it did, it would be in the form of "Wow! When will I get to use this? It's soooo cool!"

All of this is to say: I believe that math teachers should worry less about trying to answer the question and should worry more about finding ways for each student to feel that they are part of the mathematical world. For some it might take applications, for others it might take games, and for others it might actually take old-fashioned algebra problems. Whoever the student there should be some mathematical or mathematical-like idea that resonates with them. And then once we have a place to start with each student we can begin to introduce them to the next idea and so on and so on. Let's stop worrying so much about answering "the question" and start spending more time finding mathematical ideas that each student can call their own.

All of this is to say: I believe that math teachers should worry less about trying to answer the question and should worry more about finding ways for each student to feel that they are part of the mathematical world. For some it might take applications, for others it might take games, and for others it might actually take old-fashioned algebra problems. Whoever the student there should be some mathematical or mathematical-like idea that resonates with them. And then once we have a place to start with each student we can begin to introduce them to the next idea and so on and so on. Let's stop worrying so much about answering "the question" and start spending more time finding mathematical ideas that each student can call their own.